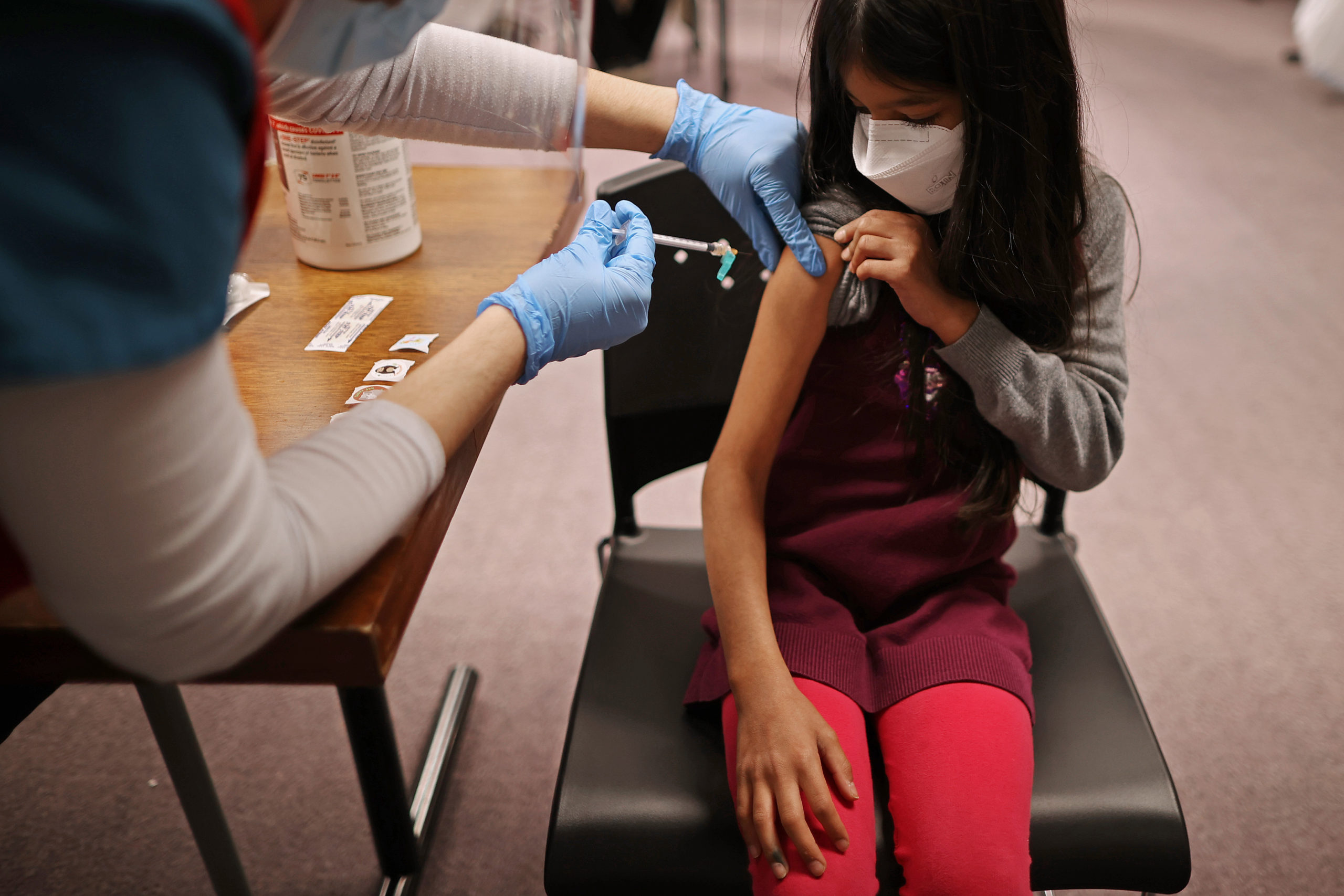

Kids are behind on routine immunizations. Covid vaccine hesitancy isn’t helping.

That worries pediatricians, school nurses and public health experts that preventable and potentially fatal childhood illnesses, thought to be a thing of the past, could become more common.

“We just want to keep measles, polio, and all the things we vaccinate against out of the political arena,” said Hugo Scornik, a pediatrician and president of the Georgia Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He was alarmed by the introduction of several bills in the state legislature over the past year to restrict vaccinations, including one that would end vaccination requirements in schools. Several states considered similar legislation that would have removed or removed school vaccination requirements, though none made any headway.

At the start of the pandemic, childhood vaccination rates plummeted. In 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention saw a 15 percent drop from pre-pandemic levels in states’ orders for Vaccines for Children, the federal program that immunizes about half of the country’s children. In 2021, order levels were about 7 percent lower than pre-pandemic levels, according to the CDC.

In Florida, where the surgeon general announced last month that healthy children may not benefit from Covid vaccines, the 2-year routine rates for all immunizations at county-run facilities fell from 92.1 percent in 2019 to 79.3 percent. in 2021.

In Tennessee, nearly 14 percent fewer vaccine doses were given to children under 2 years of age in 2020 and 2021 than before the pandemic.

And in Idaho, the number of children who received their first dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR) at age 2 fell from about 21,000 in 2018 and 2019 to 17,000 in 2021.

Immunization proponents say polarized attitudes to the Covid-19 injection have made holding and promoting school-based immunization events more difficult as principals and school nurses navigate the fraught terrain of building trust within their communities while at the same time encourage vaccination. That makes it more difficult for children to get their injections, even if their parents want them to be vaccinated.

Between 2010 and 2020, the last year for which national data are available, vaccination coverage in children under 3 for hepatitis B, polio, chickenpox and MMR fluctuated around 90 percent and remained largely unchanged, while rates for pneumonia and rotavirus vaccines significantly increased. Meanwhile, the percentage of children without injections grew from 0.6 percent to 1 percent. The CDC is expected to release new data next week on national preschool immunization rates in 2020-2021.

Parents who were hesitant to vaccinate their children before the pandemic are now being joined by people who believe the government has mishandled the crisis, view Covid-19 vaccine mandates as federally overstated, or are exposed to misinformation about vaccinations in children, said Rupali Limaye, professor of International Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“You get a decline in trust in your government and people looking to other sources to inform their decision-making process,” she said. “So they go to social media, [where] misinformation trumps evidence-based information.”

Immunization advocates say it was easier to fight false claims that caused pre-pandemic hesitation, such as that vaccines cause autism. But it’s harder to resist an argument about personal freedom from government mandates.

“I would have told you in April 2020 that now would be our time to turn the anti-vaccine tide,” said Melissa Wervey Arnold, CEO of the Ohio Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Unfortunately, the freedom movement took over.”

According to the CDC, only about 45 percent of eligible children in the US have received at least one dose of Covid-19 vaccine.

“Parents are starting to come in with the same questions they had with the Covid-19 vaccine,” said Nola Jean Ernest, a pediatrician in Enterprise, Ala., and president-elect of the Alabama Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “‘Is it worth it? Do my kids need this vaccine?’ That is the hesitation that is beginning to bloom.”

So far there hasn’t been a spike in preventable childhood illnesses, but public health experts fear it’s only a matter of time if they aren’t able to raise vaccination rates in a meaningful way. In 2019, the US reported the most measles cases in 27 years, with outbreaks clustered in parts of New York and the Pacific Northwest with low vaccination rates.

“‘Is it worth it? Do my kids need this vaccine?’ That is the hesitation that is beginning to bloom.”

Part of the challenge for public health experts looking to anticipate the next outbreak or find vulnerable communities is that the availability of current vaccination data varies widely from state to state.

Heather Gagliano, director of operations and education for the Idaho Immunization Coalition, said data delays make it difficult to demonstrate the magnitude of the problem.

“In my years with vaccinations, I’ve seen people who have always worried,” Gagliano said. “But there were really very few. I am concerned that it will become much more mainstream in that conversation where misinformation and misinformation are somehow more accepted as the truth than before.”

Data on waiver requests — another insight into how many families choose not to vaccinate their children — is also slow. But the information out there shows that a small but increasing number of families are opting out of vaccination in some states.

In North Dakota, religious, moral, and philosophical waiver requests rose from 3.6 percent in the 2019-2020 school year to 4.46 percent for the current school year.

In South Carolina, which only grants exemptions for religious, not personal, beliefs, the number of exempt students has steadily increased over the past five years, from 1.2 percent in the 2017-2018 school year to 2 percent this year.

A spokesperson for the South Carolina health department declined to comment specifically on the reasons for the changing vaccination patterns, but said “there are many factors and trends involved.” But Amanda Santamaria, director of nursing services for Dorchester School District Two in Summerville, SC, and president of the South Carolina Association of School Nurses, believes parents are now exploring vaccines in new ways.

“It has prompted people to look at vaccines in general for students and for children under a finer microscope,” Santamaria said.

Pediatric health professionals believe there is more information circulating about how to circumvent vaccination requirements through waivers, contributing to lower-than-usual immunization rates.

“It used to be very rare for a religious exemption,” said Kimberlee Wyche-Etheridge, senior vice president of health equity and diversity initiatives at the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and a pediatrician in Nashville. “Now that option seems to be on the table.”

In places like Colorado, Louisiana, Mississippi and New York, state health officials and pediatricians say they see no noticeable difference in parents’ attitudes toward immunization or in their available data.

There has always been a small group of parents who oppose childhood vaccinations, but if doctors can get parents to the office and answer their questions, they can usually convince them to get their children vaccinated, said Eric France, a pediatrician and medical director of the Colorado Department of Health and Environment.

But in many parts of the country, the pandemic has affected parents’ views on vaccinations in ways states should not ignore, warned Patsy Stinchfield, a pediatric nurse who worked as an infectious disease vaccine specialist at Children’s Minnesota, a nonprofit organization. children’s hospital and elected president of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. In Minnesota, more than a third of 2-year-olds in 2021 were unaware of their vaccines.

“It’s worth all states, both in the private and public sectors, to pay extreme attention and put extreme effort into this problem because it won’t solve itself on its own,” she said.

When it became clear that children were lagging behind on vaccines, the CDC, as well as other national organizations such as AAP, launched campaigns to encourage parents to catch up, said Georgina Peacock, acting director of the CDC Immunization Services Division.

During the pandemic, the CDC has provided grants to community organizations across the country to increase Americans’ confidence in vaccines. The agency has also hired and trained vaccine demand strategists, health officials and adult immunization coordinators to help state health departments promote Covid-19 vaccines and, increasingly, routine immunizations.

But immunization proponents are concerned that the anti-vaccination movement will grow stronger without more work to combat the general hesitation about vaccines.

Some vaccine proponents are finding it increasingly difficult to do outreach. Santamaria, in South Carolina, said her school district has promoted school-based vaccine clinics as a program offered by the district — rather than individual schools — to protect principals and school nurses from anti-vaccination.

Erica Harp, chief nurse at Great Falls Public Schools in Great Falls, Montana, said she is cautious with her immunization advocacy these days.

“Vaccination used to be something the school nurse always advocated and spoke to, and I hope we can continue to do that,” Harp said. “You always worry about how you are seen in the community… Our schools are not required to have school nurses. You always try to make sure you protect your job, almost.”

Comments are closed.